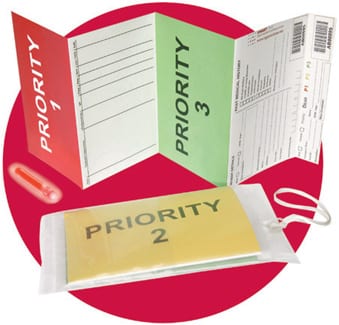

During my CEO decision-making series, I’ve talked about how to thwart the four villains of decision-making and 10 rules to live by, but what do you do when you are in the heat of battle and decisions are lobbed onto your desk? Something that I have found helpful is to have a “triage procedure” where you sort decisions into one of three categories based on their impact on the business:

- Insignificant: The answer won’t impact the business

- Easy and significant: Not a close call but important to get it right

- Difficult and significant: No clear answer but the decision will make a difference to the business

Here’s how I treat each issue:

Insignificant decisions present coaching opportunities

For insignificant problems I force the person bringing me the issue to make the decision and explain to me how they arrived at their conclusion. I never change their decision, but I may coach them on their thought process. I want to be sure that they are considering all stakeholders in their decision process. It is a great opportunity to do some coaching on the values of the company in a no-risk situation. I want them to gain confidence in making decisions, so I don’t change it even if it is very different from the solution I would have proposed.

Easy but significant decisions require executive input

The approach for easy but significant decisions is slightly different. Since the decision could have a significant impact on the business, you must make sure that the final decision is correct. I reach a decision based on my knowledge and then, if the decision affects multiple groups, I engage all of the appropriate executives individually to find out what decision they would make. If any of the executives have a different opinion, this could indicate a misalignment of values. Conversely, they may have additional information on the problem that sheds new light on the issue. This process either leads to a consensus decision or a new decision strengthened by additional information.

Difficult and significant decisions: Determine level of risk

The last category of decisions is by definition hard since the decision could have a major impact on the business. I split this category into two sub-areas based upon how easy the decision is to correct if the wrong decision is made.

Low-risk decisions: Some decisions, while significant, may be relatively easy to reverse and therefore carry much less risk. For the low-risk category, the CEO should focus on making a quick decision that allows the organization to move quickly. Other decisions, such as doing a major acquisition, are almost impossible to reverse and therefore carry tremendous risk.

Hard, significant and risky decisions: These decisions can determine the ultimate success of a CEO. Obviously, there is no magic pill for them. When you talk to CEOs about these kinds of decisions, they will often refer to relying on their gut instinct or a special feeling that something was the right course. I have found it critical to get the perspective of people who are not emotionally attached to the decision. Often, their wider perspective will provide a better path forward than those who are in the heat of the battle. Reaching out to mentors and peers who have experience can provide key insights that might otherwise be neglected.

How outside perspective helped me make one of the biggest decisions of my career

For example, one of the biggest decisions of my business career involved negotiating the sale of NetQoS, a company I co-founded. After a little back and forth with the acquirer, we had received a “final” cash offer of $180 million. It was in May of 2009 and the economy was still sputtering. M&A activity was near an all-time low as companies hoarded cash in the face of the recession.

We had set a goal of selling the company for $200 million, so the question was whether to take the offer as is or walk away from the $180 million and hope the acquirer would raise the offer. There were no other acquirers in sight, so if they didn’t raise their offer we would have missed out on a big deal.

I owned a significant position in the company, so from a personal perspective it would have been easy to take the 180 and declare victory. However, something bothered me about settling for an offer that – while reasonable – was short of the goal. I reached out to the members of a CEO peer group that I was a member of for guidance.

Without revealing the acquirer, I was able to walk them through all the issues involved. While more of them would have taken the 180 than pass, the process of talking through the issues with a group that was not emotionally connected to the transaction provided the clarity I needed. I recommended to the board that we pass on the offer. Six weeks later the acquirer returned to the table with a $200 million offer. While things could have turned out differently, I was comfortable that I had made the best decision possible and could have lived comfortably with either outcome.

I hope this triage approach and all of the decision-making articles I’ve shared will help those of you in a position to make decisions that impact your companies in small and large ways.

Related articles:

- 10 Rules of CEO Decision-making: Part 1 (theamericanceo.com)

- 10 Rules of CEO Decision-making: Part 2 (theamericanceo.com)

- 10 Rules of CEO Decision-making: Finale (theamericanceo.com)

- Which Decisions Should a CEO Make? (theamericanceo.com)

0 Comments